ON 24 MARCH 2016, A PALESTINIAN WAS LETHALLY SHOT BY AN ISRAELI soldier in downtown Hebron, in the occupied Palestinian territories. The event was captured on camera.1 The footage was clear, filmed by a Palestinian neighbor from his adjacent roof, and the shot was audible.2 The soldier could be seen methodically cocking his weapon as he approached his Palestinian target, an assailant who was already lying immobilized on the ground, and firing a single bullet at close range. The footage quickly went viral in Israel, played and replayed on the nightly news, dominating social media. The three-minute video would be committed to Israeli national memory.

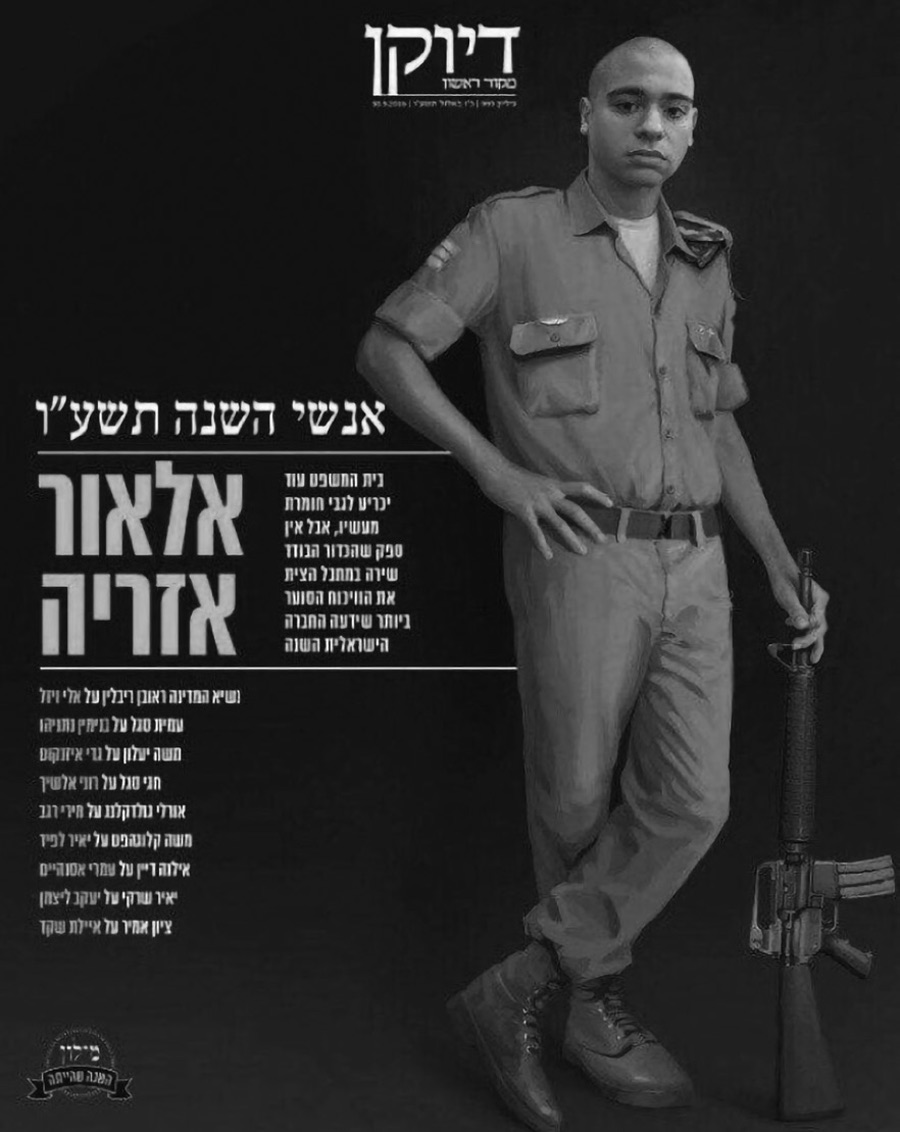

Few Israelis knew the name of the slain Palestinian, Abdel Fattah al-Sharif. All knew Elor Azaria, the soldier. Azaria’s trial in Israeli military court captivated and polarized the Israeli public, a national media spectacle that many likened to the OJ Simpson case in scale and symbolic import.3 Military leadership supported the legal process in the name of their “ethical code.”4 In an unprecedented break with their military, most Jewish Israelis disagreed.5 Thousands demonstrated in solidarity with Azaria in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square, demanding his exoneration in the name of “everyone’s child.”6 “If we don’t protect our soldiers,” their posters read, “who will protect us?” One prominent Israeli magazine named him “man of the year,” decorating its cover with his smiling portrait (Image 2).7 Azaria would be convicted of manslaughter in Israeli military court in 2017—the first such conviction of an Israeli soldier in more than a decade—but released from prison after serving nine months of his sentence.8 He was greeted with a hero’s welcome.9 Azaria’s celebrity status would grow in months and years hence, coveted for election endorsements, welcomed in Tel Aviv nightclubs and West Bank settlements by cheering crowds.10 Within the voluminous Israeli national debate that the incident spawned, Israel’s status as an occupier was not open for popular discussion. On this, there was no real disagreement.

The case was deemed a landmark for the ways it pitted the Jewish public against their military, the nation’s most sacred institution. It was also a milestone in another sense. Although cameras were prolific in the West Bank in 2016, footage of this sort remained a rarity—that is, footage of Israeli state violence that captured both the military perpetrator and Palestinian victim in the same frame: “Azaria was not the first, nor will he be the last, Israeli soldier during the violence of this past year to shoot a Palestinian attacker who no longer posed a threat,” wrote one Israeli left-wing commentator. “But he was the only one to find himself caught on film so blatantly . . .”11 For Palestinian communities living under occupation, the case was yet another incident of military violence with legal impunity, for which there was considerable precedent. Azaria was the occupation’s rule, they argued, not its exception. Mainstream Israeli Jews, for their part, read it as a parable of the Jewish state, an illustration of their existential battle against enemies that sought their demise. Through the viral frames, all had told their own story of Israeli military rule.

Screen Shots is a social biography of state violence on camera, studied from the vantage of the Israeli military occupation of the Palestinian territories. My historical context is the first two decades of the twenty-first century, a period when consumer photographic technologies were proliferating globally, chiefly in the form of the cellphone camera, even as communities across the globe were growing increasingly accustomed to life under the watchful eye of cameras. At the core of this study are the various Israeli and Palestinian individuals and institutions who, living and working in the context of the Israeli military occupation, placed an increasing political value on cameras and networked visuals as political tools: Palestinian video-activists, Israeli military and police, Israeli and international human rights workers, Jewish settlers. All trained their lens on the scene of Israeli state violence—some to contest Israeli military rule, others to consolidate it. Screen Shots examines this broad field of photographic encounters with Israeli state violence in the occupied Palestinian territories, attentive to political interests they both displayed and disguised, to the political fantasies they both mirrored and mobilized. I am interested in what these encounters reveal about the Israeli and Palestinian colonial present in the digital age and what they suggest about possible futures.12

The communities and institutions studied in this book have very different histories behind the lens. Palestinian and Israeli activists and human rights workers would be among the first to adopt cameras and networked visuality as political tools. Israeli military spokespersons would follow, as would (belatedly) Jewish settler communities. Their political aims were radically divergent, as was their access to the technologies, infrastructures, and literacies of the digital age. And yet, across these radical divides, many shared a version of the same camera dream. Many hoped the photographic technologies of the digital age—with the scene of state violence now visible at the scale of the pixel, circulated in real time—could deliver on their respective political dreams. Some, particularly the Israeli state institutions among them, harbored a techno-deterministic fantasy that technological progress (smaller, cheaper, sharper, faster) and political progress were mutually enforcing. All hoped that these new cameras could bear truer witness and thus yield justice as they saw it.

Most would be let down. Israeli human rights workers would painfully learn this lesson: even the most abundant visual evidence of state violence typically failed to persuade the Israeli justice system or Israeli public, as the Azaria case would make spectacularly visible. Palestinian video-activists living under occupation had additional frustrations, rooted in the everyday violence of military rule. Contending with poor internet connectivity and frequent electricity outages, byproducts of the occupation itself, they found that their footage often failed to reach the international or Israeli media for on-time distribution. Or they often faced punitive and violent responses from soldiers at checkpoints, sometimes taking aim at cameras and memory sticks. And even the military grew frustrated. Their footage from the battlefield seemed to be perpetually inadequate and belated, military analysts lamented, always lagging behind their digitally savvy foes. They dreamed of a more perfect public relations camera that would finally redeem their global image. The fantasy was perpetual, the dream always deferred. Screen Shots lingers here, on this wide range of broken camera hopes and dreams, born of very different histories and conditions, distributed across the political landscape of Israeli military rule.

Much of this is not new. Photography has been interwoven with the political struggle over Palestine since the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the early decades of both Zionist settlement and commercial photographic technologies.13 Nor are the themes of this book unique to this geopolitical case. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, as mobile digital technologies proliferated, political hopes and dreams across the globe were famously attached to the ostensible promise of digital photography. The Arab revolts, the Occupy movement, the Syrian revolution, Black Lives Matter: each depended on the internet-enabled camera as a tool of citizen witnessing.14 Many of these social movements would be represented in the media by photographs of crowds holding their cellphone cameras aloft. The image of digital camera phones held skyward would consolidate as a justice icon, a highly recognizable symbol of popular protest (Image 3).

When these social movements confronted their respective limits—as when livestreams from Syria failed to stem the bloody state crackdown, or when bystander footage of US police shootings failed to produce convictions—digital dreams also faltered. The global rise and spread of surveillance states in these decades, alongside governance-by-data, would further erode the investments of a prior generation of activists and scholars in paradigms of “liberation technology” and “digital democracy.”15 The global Black Lives Matter protests against police violence that erupted in the summer of 2020—ongoing as this book went to press—would reignite popular investments in the radical potential of the by-stander camera as a tool of social change.

At the core of this book, as the opening vignette suggests, is the entanglement of consumer photographic technologies and Israeli state violence. By the end of the period chronicled here, this entanglement had become ordinary, both in Palestine and globally. It bears remembering that it wasn’t always thus. As recently as two decades ago, the presence of the bystander camera at the site of state violence registered as anomalous and shocking: the Rodney King beating in 1991; the torture at Abu Ghraib prison in 2004; the killing of Neda Agha-Soltan by Iranian paramilitary forces in 2009. In each case, the camera’s presence on the scene was part of the ensuing public shock. Media commentators on the King beating by the Los Angeles police stressed the disquieting coupling of police brutality and “home video” technologies ripped from private contexts.16 In the aftermath of the Abu Ghraib revelations, much would be written about the ways that ordinary “point and shoot” cameras were now proliferating in the hands of the US military, changing the terms of soldiering.17 Then, these bystander cameras were thought to be jarring: technologies out of place. Much would change in the two decades hence. By 2016, the time of the Azaria shooting with which this book begins, YouTube was functioning as a dense visual repository of Israeli state violence, shot from multiple perspectives and angles, largely by Palestinian activists and bystanders. The eyewitness camera had become an anticipated feature of the landscape of state violence.

Camera technologies have long been tethered to social and political dreams of various kinds—particularly, the historically recurrent fantasy that new photographic innovations will succeed where older ones failed: that is, the dream that they will effectively mediate less, finally ensuring transparency. These hopes and dreams resound with particular frequency and urgency in contexts of war or violent conflict when social demands on witnessing are heightened. Equally recurrent is the lament that follows when these dreams fall short, when these new media fail to stem violence or deliver justice. Taking the Israeli occupation as its case study, Screen Shots chronicles the range of political investments that were animated by the new photographic technologies and networked platforms of the early digital age and the conditions under which they faltered. This is a story of camera dreams, and camera dreams undone.

1. B’Tselem, “Video: Soldier Executes Palestinian Lying Injured on Ground After the Latter Stabbed a Soldier in Hebron”; Roth-Rowland, “Nobody Should Be Shocked at the Hebron Execution.” For an analysis of this case within a critical legal context, see Diamond, “Killing on Camera.”

2. The photographer was Imad Abu Shamsiya. He would experience abuse and intimidation after the footage aired. Marom, “The Camera That Made Elor Azaria ‘Man of the Year.’”

3. Galdi, “Everyone’s Favorite Murderer.”

4. Bob, “IDF Finds Ambulance Driver Tampered with Knife After Shooting of Hebron Attacker.” On the legal history of this exculpatory military narrative, see Diamond, “Killing on Camera.”

5. Cohen, “Hebron Shooter Elor Azaria Sentenced to 1.5 Years for Shooting Wounded Palestinian Attacker”; Kershner, “Israeli Soldier Who Shot Wounded Palestinian Assailant Is Convicted”; Omer-Man, “Nearly Half of Israeli Jews Support Extrajudicial Killings, Poll Finds.”

6. Cohen et al., “Thousands Rally for Soldier Who Shot Palestinian Assailant.”

7. Marom, “The Camera That Made Elor Azaria ‘Man of the Year.’”

8. Cook, “Elor Azaria Case”; Kubovich and Landau, “Elor Azaria, Israeli Soldier Convicted of Killing a Wounded Palestinian Terrorist, Set Free After Nine Months”; Omer-Man, “Extrajudicial Killing with Near Impunity.”

9. Konrad, “Elor Azaria and the Army of the Periphery.”

10. Harkov, “Likud Deputy Minister Enlists Elor Azaria in Primary Campaign”; Livio and Afriat, “Politicised Celebrity in a Conflict-Ridden Society.”

11. Marom, “The Camera That Made Elor Azaria ‘Man of the Year.’”

12. Gregory, The Colonial Present.

13. Behdad, Camera Orientalis, Nassar Photographing Jerusalem; Sela, Made Public; Sheehi, The Arab Imago; Silver-Brody, Documenters of the Dream.

14. Della Ratta, Shooting a Revolution; Richardson, Bearing Witness While Black; Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas; Wall, Citizen Journalism; Wessels, Documenting Syria.

15. Scholarship under these headers would also proliferate in the 1990s and early 2000s. See, for example, Akrivopoulou and Garipidis, Digital Democracy and the Impact of Technology on Governance and Politics; Ziccardi, Resistance, Liberation Technology and Human Rights in the Digital Age. Adi Kuntsman and I discuss this in greater detail in Digital Militarism.

16. Adams, “March 3, 1991: Rodney King Beating Caught on Video.”

17. Sontag, “Regarding the Torture of Others.”